Voice of the people: Hong Kong saves its beloved multicultural karaoke bar

Legendary Junels Restobar survives eviction, protests and a pandemic to serve up Filipino food, drinks and a multilingual song list to loyal regulars

By Chad de Guzman

April 2020

It was 7:30 pm on a Saturday in April. The fluorescent sign for Junels Restobar lit up On Ning Lane—a dark alleyway in Sai Ying Pun—like a beacon for the occasional passerby. The establishments flanking the bar were closed. A stone statue of a chef, its paint chipping, stood guard. Saturday nights are usually busy in Hong Kong but tonight the city was quiet.

Inside, 63-year-old owner Julia Mangrobang sat hunched over a Candy Crush game at the table farthest from the entrance. Her eyes crinkled at the corners in greeting, the only sign of her usual smile, now hidden behind a surgical mask.

I took the table next to hers more than a meter and a half away to ask how business was. “The usual,” she answered in a motherly voice, even though it was far from it. The only other sign of life was the 80s rock hits playing from an iPod Nano plugged into her sound system. The flat-screen TVs bolted to every wall were off. The lone karaoke machine was tucked away above the refrigerator, and the songbook and microphones usually on display were nowhere in sight.

Her phone rang. She did not recognize the number but picked up anyway.

“Ate Julie, this is Max,” the man on the phone said in Filipino.

Her eyes widened in recognition.

“Are you open?” he asked.

“Yes,” Julie said, a lilt in her voice.

Max asked if they could come in around 10:30 pm, to which Julie gleefully answered, “No problem.” She then suggested they place their food order before arriving.

I asked if she knew all of her regular customers’ names. Julie said she never forgets a face, though sometimes her husband Alvin helps. Two Filipino men in their twenties entered as if on cue. She called on the taller one, Joseph, and they waved at each other before she excused herself from our conversation.

Junels Restobar is a neighborhood restaurant and late-night bar serving Filipino comfort food and cheap drinks. But it’s best known as the most beloved karaoke bar in town.

When the novel coronavirus, now known as COVID-19, first hit Hong Kong in January, the city acted quickly. The new virus shared the genetic make-up of a ghost that previously haunted Hong Kong: SARS, which killed almost 300 in the spring of 2003. The streets emptied almost overnight.

The Hong Kong government closed “karaoke activities” in all bars and restaurants on April 1. The day before, five locals singing in the Red MR karaoke lounge branch in Tsim Sha Tsui tested positive for COVID-19.

It wasn’t just karaoke. Gambling and horseraces ceased operations. Beauty salons, massage parlors and bars shut down. Restaurants operated at half-capacity. Many small family businesses closed up shop, some for good.

But Junels doors stayed open.

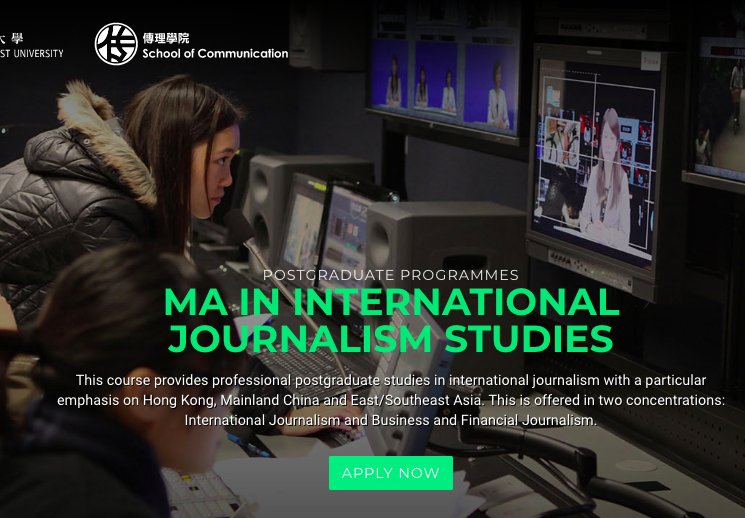

Julie Mangrobang stands outside Junels Restobar in Sai Ying Pun.

Julie first opened the restaurant’s doors in 2009 in Lai On Lane, a small sunken alley just one block over from the current location, in the same building where she used to live. Its first home was nestled between a shop selling used carton boxes and another selling kitchenware. A signboard jutting out was the only way to spot it from the main road.

The restaurant was Julie’s brainchild with her old friend Nelson Orquico. Though Julie is the one who pushed through with the business alone, the name “Junels” is a blend of the names Julie and Nelson.

Her landlord badgered her for three months to rent the space beneath their flat, she said.“It was a lengthy courtship,” she said. “My landlord was courting me, persuading me to open a business.”

Julie has been working in Hong Kong since she arrived from the Philippines in 1984. First, she was a domestic helper for four years before jumping to waitressing, which she did for another 14. Yet her entire life savings were still not enough to start a restaurant, so she and her son took out bank loans.

Her goal was to open a karaoke spot to meet the demand from Filipinos singing in Hong Kong’s streets. The idea came to her when someone tried to sell her a karaoke spot in the Li Yuen streets, known as “Alley-Alley 1” and “Alley-Alley 2” by Filipinos looking for a quick music fix.

“But I got word that it was disorderly, and you would not be able to acquire a business license,” she said.

More than 200,000 Filipino domestic helpers work in the city, according to government statistics. Thousands of them spend Sunday, often their only day off, hanging out in Central’s network of alleys and alcoves, each pocket group marking their territory with cardboard, many with portable speakers and microphones in hand. Once settled, they connect their phones to sing “Pinoy” pop music and 80s ballads. But there’s one classic that is heard more than any other song:

Just another woman in love

A kid out of school

A fire out of control

Just another fool

Anne Murray’s 1984 hit “Just Another Woman in Love” was so popular with Filipino karaoke singers that a Filipino cover was made. The lyrics are different, but the context remains the same:

Ikaw ang tunay na pag-ibig (You are my one true love)

At minamahal (And the one I adore)

Bigyan ng halaga (I will value you)

Ipaglalaban (And will fight for you)

The songs resonates with the Filipina overseas worker: a woman who loves with much fervor, who will do everything to make her loved ones happy even at the expense of being away from them.

Sociologist Jonathan Ong said in his 2009 study that singing karaoke for Filipino migrants in particular is a way to interrupt everyday experiences. With overseas workers’ daily toil, these domestic helpers look forward to these “red-letter rituals” with friends and family in spaces where they can come together.

“Located in living room space and observing ‘holiday time,’ Filipinos proactively strive to recreate the homeland through symbols and rituals in food, talk, and song,” he wrote.

Music is pervasive in Filipino culture. In family gatherings, parents coerce their children to sing. Across farmlands and cities, electric lampposts bear advertisements for portable karaoke TV rentals for parties. Wireless microphones with a number pad to input song choices can be found in both shanties and mansions. The New York Times even reported a series of killings in Manila related to off-tune karaoke renditions of Frank Sinatra’s “My Way” in 2010.

Karaoke is a big deal to Filipinos, and Julie was going to make money out of it.

Jarius King’s first experience at Junel’s was much the same for every eventual regular.

A 35-year-old DJ and arts educator, Jarius moved from Chicago to Hong Kong in 2015. Soon after his arrival, his friend and booking agent Moon called to meet up in Junels to talk business. Jarius had never heard of the place, and it would take him an hour on the train to get there.

“When I tell you about this place, you’re gonna have a good time,” he remembered Moon saying.

Jarius wandered the Sai Ying Pun neighborhood looking for Junels. When he finally found Lai On Lane, the dark, half-hidden alley looked like a space for trash bins. The façade was just a dingy hole in the wall. A banner hung across the doorway: Junels Party Place. There was just enough light inside to see people moving but not enough to see their faces.

As he squeezed through the door, a familiar sound blared from the speakers. It was the dialogue from a “teleserye,” the Filipino counterpart to the Spanish “telenovela” known for its over-the-top family in-fighting and rags-to-riches stories. Jarius would know that sound anywhere. His Mexican and Puerto Rican mates back home played them all the time.

“I thought this was a karaoke spot?” he called to Moon, who was waiting for him.

Jarius worked his way between the row of tables on his left and the bar counter on his right. As he inched forward, he sensed the room grow bigger and brighter. Suddenly, Jarius felt warm. He was transported back to Chicago, to the comfort of his living room. It didn’t matter to him people around him were speaking Filipino. It just felt right.

Jarius noticed a small woman zipping in and out, serving and talking to customers. He didn’t speak to her except to place orders, but he will always remember how Julie smiled at everyone.

In the winter of 2016, 26-year-old Chinese-American Alison Tan found herself in a bar brawl in Junels. A British couple who gatecrashed their party wordlessly snatched the microphone from her friend’s hand. An hour earlier, the same couple had locked Junels door from the inside. No one heard Alison knocking outside for over 40 minutes.

Her “drunk and peacocking” husband, Sotiris Tsouris, charged the man. Alison jumped in to pull her husband back. In the scuffle, Sotiris knocked over a vase full of sunflowers. The vase shattered.

The singing stopped. So did the fighting.

Alvin’s voice cut the silence. “You broke my flower pot!”

Then he kicked Alison and her drunk friends out.

The next day, Alison felt horrible. The bar had been her go-to karaoke place ever since she moved to Hong Kong from Pennsylvania in 2012. Alison and her friends had difficulty finding karaoke places in Hong Kong that had the same vibe as the affordable college hangout spots they had enjoyed in the US. She always raved about the immediate warmth she felt upon seeing the Christmas décor and lights adorning the walls all year round, and she was happy to let her friends in on what she considered to be one of Hong Kong’s best kept secrets.

Music rooms in Hong Kong, such as Red MR branches and Music Box Karaoke, are on the pricier side, costing up to HK$300 a person. These establishments have 50 to 60 private singing rooms for rent, and ordering food and drinks costs extra. Klaiver Wang’s book “Hong Kong Popular Culture” says establishments like these in Hong Kong make a profit from their updated Cantopop song selection. These singing rooms partner up with varying local record labels for instrumentals of latest hits from Sammi Cheng, Francis Yip and many other local Cantopop idols. “The privilege to provide the latest songs in the bar became the most important marketing strategy,” Wang wrote.

Junels is a different ballgame. For the price of HK$45, customers can drink what’s dubbed as the Philippines’ “number one beer”: Red Horse Extra Strong with 6.9% abv. A swig usually kicks customers towards Julie, where she gives out scraps of paper and a pencil to write down a song’s number ID from a thick songbook. Updated monthly, the song library contains old American classics and Filipino staples regardless of genre, with a decent peppering of K-pop, J-pop and Cantopop.

This all reminds Alison of dive bars in the United States. She loved Junels community vibe, where everyone shares the same mic and dances to the same song. She did not want to lose access to the space.

Filled with hungover shame, Alison baked a mango crème cake and bought a box of strawberries as a peace offering to Alvin and Julie. When she arrived to apologize and offer her gifts, the Filipino couple just chuckled and told her not to worry about it. Alison offered to replace the vase they broke, but both Alvin and Julie smiled at her and said there was no need.

Though most know Junels for its karaoke, for many, the food is just as popular. “Sisig” is one of the many Filipino dishes on Junels menu. Julie says it is the restaurant’s bestseller for both Filipinos and foreigners. Contemporary versions of sisig are served on a sizzling platter, but it still hearkens back to the Spanish colonial-era recipe where the “maskara” (the nickname for the pig’s face and ears) is roasted and diced. This is mixed with chicken liver and seasoned with sour ingredients, such as vinegar, calamansi or onions. It’s the ear’s cartilage that give sisig its characteristic crunch.

This crispy, tangy, meat dish served with egg yolk always ends up on the bill for Francesca Ayala, a Filipino working in public relations in Hong Kong, since she began frequenting the restaurant in 2015.

“I make all of my friends who aren’t Filipino try it,” Francesca said, “but they try not to freak out when they find out what’s in it.”

Filipino cuisine is known for its smorgasbord of flavors and ingredients, but it is also known to promote sharing. Sisig is known as classic “pulutan,” the Filipino version of Spanish tapas. Junels deep-fried pork knuckle, so crispy and tender it can be carved off the bone, can be shared between five to six people. A deep-fried pork roll, called “lumpiang shanghai” can be shared by three to four people. Junels dishes do not exist as single-order items.

Ayala brings her friends from Thailand, Australia, England, and South Africa to try out the food and belt their hearts out. She tells her friends, mostly newcomers, that the restaurant’s premium for sharing replicates the real Filipino karaoke experience in her home country.

And when someone in her circle requests Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody”, it feels like she got a direct flight home.

“That’s my family karaoke song,” she said. “There’s no particular lyric, but it’s just the fact that it’s a song that needs to be sung by a group. And every time my family and I do karaoke, that’s our song. Everyone’s screaming over each other, the different parts and the different voices, the different harmonies. You know, it’s messy, but it’s always fun.”

Julie received an eviction notice in April 2019 with only three months to move out of the spot in Lai On Lane. Her landlord told her the building was going to be demolished and an upscale one would take its place.

A few days later, Alison, now 29, passed by Junels. Julie tearily told her they were about to close.

“Oh, really, what time?” Alison asked.

“No, I’m closing soon, permanently.”

Julie had begun packing her things, her oven already on a cargo ship bound for Manila. After investing close to HK$1 million in Junels over the past decade, she had made up her mind. At 63, she felt she had done enough for her family. She thought the eviction may be a sign from God.

But Alison had other plans. She and her husband Sotiris suggested a fundraising karaoke party so the bar could relocate to another space. They aimed to raise HK$150,000 to cover renovations and other licensing fees.

Alison explained the mechanics of fundraisers to Julie. She had seen plenty of patrons rave about Junels vibe. The fundraiser would be an opportunity to show how much the Sai Ying Pun and expat communities supported Julie’s business. Alison told Julie to think of the fundraising campaign like a bank account.

Julie didn’t know what to say. She asked for time. She sought the advice of her husband, Alvin, who told her it was her decision. She worried that only sick people with terminal illnesses should be having fundraisers. Why would she go begging for help for a personal venture?

A week later, Julie gave Alison a call.

Almost a year later, Alison sat a barstool outside Junels in the new location in On Ning Lane. She took another gulp of ice-cold Red Horse, recalling the July fundraiser.

“There was just a ton of people moshing,” Alison said. “Everyone was rocking out. They were jumping up and down, singing as a crowd. People had their arms around each other and that mix of people was as diverse as it could get.”

Alison worked to get Julie’s story out. Junels was featured in the online magazine TimeOut. Francesca helped Alison with the promotion. In the end, they raised HK$55,809 from bar regulars and visitors and Julie took out over HK$70,000 in microloans from friends. Three investors agreed to help with the rest.

The old Junels in Lai On Lane officially closed on August 5, 2019. By the end of October, the newly constructed Junels softly opened its doors. And to kickstart 2020, the restaurant had a grand reopening in January. Gone were the Christmas lights and the holiday décor, replaced by a wall-sized mirror, a fridge full of Filipino and non-local beers and brighter lights. The new Junels is sleeker but it managed to retain the old charm.

It couldn’t have been a worse time to open a business. Junels took a beating during the pro-democracy protests that rocked Hong Kong in 2019. She said earnings were down 40% since because of the demonstrations.

A few months later, the coronavirus struck. As the health crisis worsened into global pandemic, the Hong Kong government announced in March it would shell out HK$80,000 to small business owners to combat the economic downturn. Julie’s new landlord also lowered her rent by HK$10,000.

But Julie was unfazed. Deep down, she knew her regulars would find their way back.

Regular customer Jarius said it will only be a matter of time until he goes back to Junels. “I hope I have just another chance to be a regular patron again,” he said.

Outside, the sky turned dark. Peak hour were about to begin for Junels, and Julie went in and out of the bar, readying it for customers. Before the evening got too busy, Julie made her way towards Alison and clambered onto the barstool next to her friend.

“You know what, I don’t focus on the money,” she said after listening to Alison. “I focused on what she did. She encouraged me. Otherwise I wouldn’t have opened again.”

A tear slid down Julie’s cheek. Alison was quick to hold Julie’s hand and give her a tissue when she saw it.

After a pause, Julie croaked, “I really feel loved and I didn’t expect it.”

A version of this article was published by Vice on June 6, 2020.

A customer sings a Filipino favorite at Junels on a Sunday night.

Christmas lights and balloons decorate the original Junels Restobar on Lai On Lane in 2013. (Source: Junels Facebook Page)

I really feel loved and I didn’t expect it.

Everyone’s screaming over each other, the different parts and the different voices, the different harmonies. You know, it’s messy, but it’s always fun.

Julie Mangrobang waits for Junel’s Restobar customers outside her bar while tinkering with her phone. Foot traffic has gone down since the onslaught of coronavirus in Hong Kong.

People had their arms around each other and that mix of people was as diverse as it could get.

Julie Mangrobang serves drinks in her bar on a busy night at Junels Restobar.

Infree Records: connecting through music in Mong Kok

Infree Records, a music store in Mong Kok selling vinyl records, CDs, cassettes and turntables, is a place people go not only to buy music but also form relationships

Innovative Jeans Brand Unspun Brings the Future to Life in Hong Kong

3D scan creates custom fit jeans to fight fashion waste

Book collector Zheng Mingren lives a ‘life of paper and ink’

Former journalist turns 50-year book collection into store selling Hong Kong memories

Feeding Hong Kong

Charity strives to bridge the gap between food waste and hungerBy Yao RuixinDecember 2022An employee of Feeding Hong Kong counts and verifies food items collected by volunteers from bakeries. Bakery staff often provide a receipt for the amount of bread to prevent...

‘We should be seen as citizens, not as slaves’

Hong Kong’s foreign domestic helpers report abuse of the system as the pandemic exacerbates shortages and struggles