Beating China’s COVID-19 censors

China’s overseas students mobilize online to get coronavirus information into the country

By William Xu

April 2020

(Source: GitHub)

About an hour’s drive outside Los Angeles, the city of Riverside lies beside the Santa Ana River. There, in his two-story house, Weilei Zeng, a Chinese PhD student, woke up at 9am on an ordinary day in mid-February. China was fighting the novel coronavirus, officially named COVID-19, and Zeng had a job to do.

First, he checked his email. Every day he received suggestions and enquiries, usually three to four, on an open-source project about the new coronavirus he had created earlier that month. One by one, Zeng replied to them politely.

Zeng’s site, called OpenSourceWuhan, provides information, data and analyses for ordinary Chinese trying to cope with coronavirus. Instead of generating content, it collects and categorizes links to other COVID-19-related open-source projects, connecting a network of thousands of independent sites all created and maintained by Chinese online volunteers.

Volunteers like Zeng are painting a never-seen-before picture about the social responsibility and civic consciousness of China’s young generation.

Everything happened quickly. In late January, pulmonologist Zhong Nanshan confirmed on television that the novel coronavirus was contagious. A few days later, China locked down the city of Wuhan, the epicenter of COVID-19, just days before Chinese New Year, when millions normally travel across the country to spend time with family.

In less than a week, 31 Chinese provinces had declared first-level public health emergencies and banned social gatherings, suspended public transport and put most medical resources into fighting COVID-19. “If you visit other people today, the virus will visit you tomorrow,” a slogan in a rural area said.

Trapped at home, many Chinese people urgently looped through TV news and went online to find out what was happening. But many realized the information they were getting was being censored. They wanted to protect themselves and to do that, they knew they needed the full picture.

This is where Zeng and other young Chinese, many of them overseas students, came in. They recognized there was an information problem in China and reached out to friends at home.

“I didn’t think too much at the beginning,” Amo, a game developer in her 20s who doesn’t want to reveal her full name, said in an online interview.“ I just wanted to see what projects were available online and what I could do.”

Based in Chengdu in southwest China, Amo started an open-source project she named Academic-nCov to post the latest overseas information, both academic and non-academic, about COVID-19.

Academic-nCov is maintained on GitHub, the world’s largest community of coders. Of its 40 million users, 31 percent of its Asian contributors come from mainland China, according to GitHub, making it a hub for Chinese online volunteer groups during the outbreak. And GitHub allows for both private and open-source projects, meaning if allowed, code can be available for anyone to use as they like, which fosters collaboration.

Every day, her team, dominated by overseas Chinese students, searched for information about COVID-19 on the Internet. From international medical journal articles to news published by foreign media, Amo’s team gathered content, mostly written in English, and translated it into Chinese.

“Providing timely information about the coronavirus from abroad for people inside China,” Amo said, “is the project’s responsibility.”

Starting on Jan. 28, Academic-nCov issued daily global briefings of five to 10 articles.” As of April 22, Academic-nCov has released 55 issues.

“All translations should be finished before 2 pm every day,” Amo said, “and the typographic design should be done in the next four to six hours.”

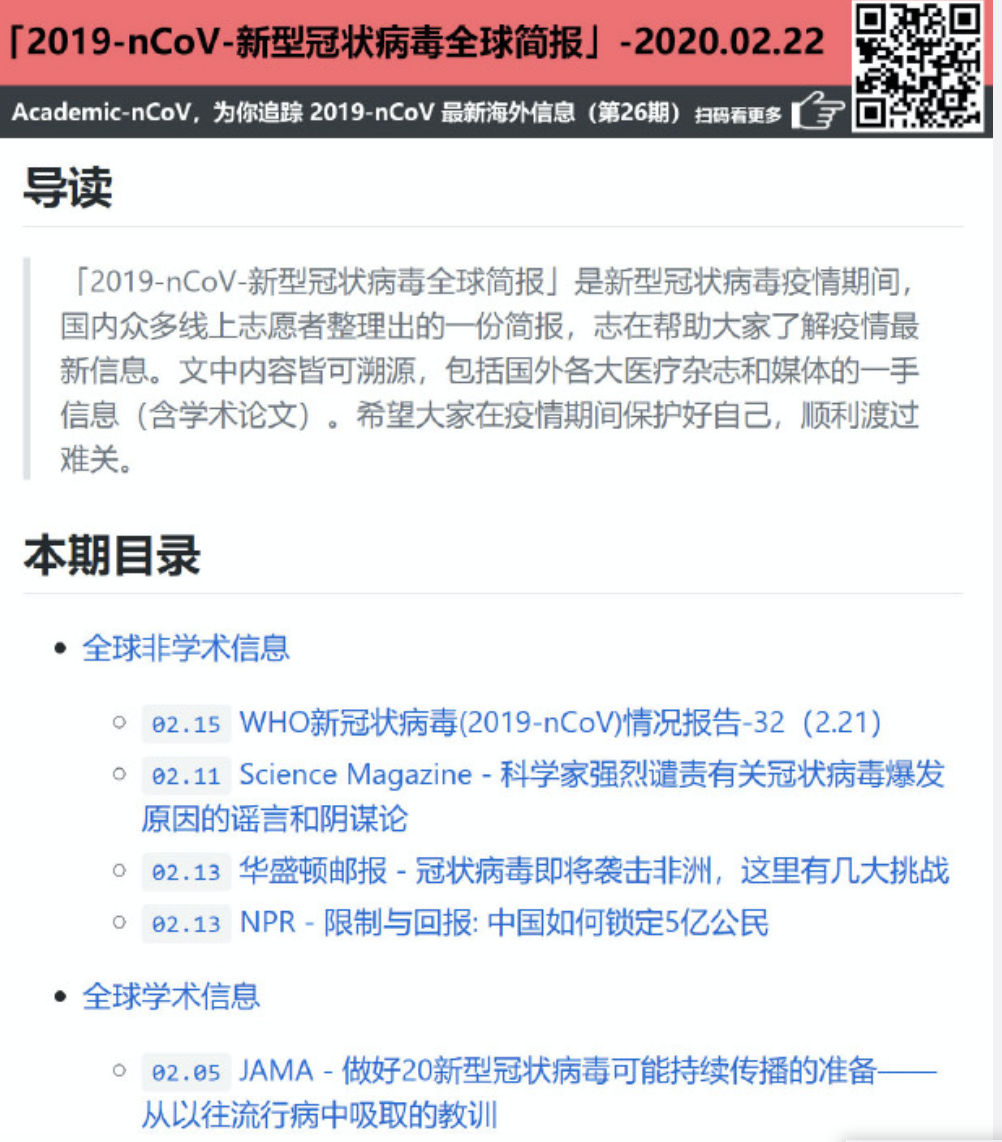

Take issue 26 as an example: It includes an article from the Journal of the American Medical Association titled “Preparation for Possible Sustained Transmission of 2019 Novel Coronavirus” Lessons,” a WHO report and three news stories from Science Magazine, The Washington Post and National Public Radio.

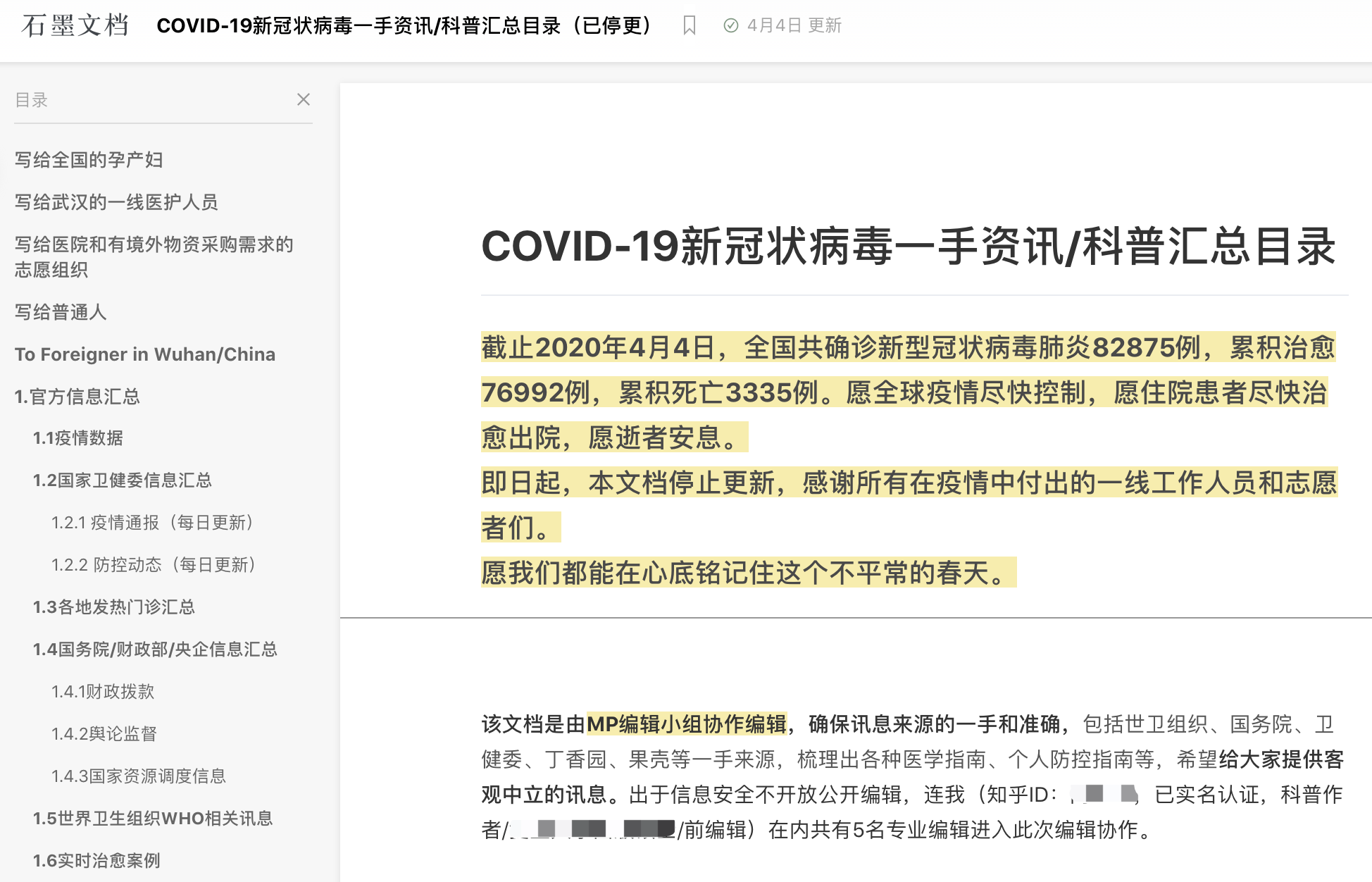

About the same time Amo began her work, A Xia, a popular-science writer, launched her open-source project called COVID-19 Catalogue of Firsthand Information & Popular Science Articles. A Xia, who also does not want to reveal her full name, said the project collects official news, guidelines for medical professionals and individual prevention as well as information on offline volunteer projects. It also busts rumors and includes some of her own writing based on medical guides, she said in an email interview.

The first edition got more than 10,000 reads within 24 hours, she said. Soon, her success attracted Guokr, a Chinese social site sharing scientific knowledge and discoveries, to ask for her permission to reproduce the issue. Guokr also sent two editors, one medical and one psychology, to help with the project. Two editor friends and nine students from her alma mater also joined. A virtual team was born.

“Maybe we don’t have much communication, or even don’t know each other before, she said, but I think everyone, firstly, agreed on what I was doing,” she said. “And secondly, everyone really wanted to do something.”

As Zeng, Amo and A Xia tried to increase understanding of the virus, others worked quickly to preserve information removed by China’s censors.

China’s internet regulations say that content producers cannot publish anything with “improper comments on natural disasters, major accidents or other disasters.” This can be hard to decipher, and China’s censors regularly delete content from websites and social media.

Franklin Han and his team founded the project Memory of 2020 nCoV: Media Coverage, Non-fiction Writings, and Individual Narratives to collect in-depth news reports and personal narratives about the COVID-19 .

Han, who is an undergraduate journalism student in Hong Kong, said he attaches great importance to the construction of a database. “I think recording history is a valuable and meaningful thing,” he said in an online interview.

Volunteers in Han’s team look for in-depth stories and features published by mainland media, which they back up with screenshots and documents. Then, team members put the article back-ups into a sort-by-date table on GitHub, which looks like a clipboard to some extent.

Han said the Chinese government was unable to control public opinion in the beginning of the outbreak. “The dawn of press freedom appeared,” said Han. “Many journalists stood out and wrote excellent reports.”

Sometimes, the team races against the censors. “We noticed that some articles had been deleted or modified very soon after publishing,” Han said. For example, one article about Li Wenliang, the doctor who tried to warn about the outbreak in late December and then died from COVID-19, was edited only 20 minutes after they saw it, he said.

Han’s project lists over 200 articles from twenty-some media. A few of these stories were removed from the Internet and can now only be viewed as back-ups. In addition to Github, the database was published on Shimo, a mainland-based online document service provider.

In Beijing in January, Hannah Yeung created a Telegram channel she called the Cyber Graveyard of Epidemic News. She worked with a partner to sort out media news and individual social posts that were removed or altered under pressure from the internet regulation body.

The first article she posted was a Weibo post saying a hospital in Wuhan was suspected of receiving inferior protection suits. “The deleting speed was so fast,” she said in an online interview, “and digital content can be easily erased.”

Her Telegram channel had over 16,000 subscribers with more than 700 posts, photos and videos in her “digital graveyard.”

Yeung said she welcomes information from others, but contributors need to prove that the content they provide has already been censored. “I do not collect political articles,” Yeung said, “and those with low credibility are not included, either.”

Yeung based her channel on messaging app Telegram because it is encrypted and has 400 million users. Though Telegram is officially blocked in China, many Chinese are able to access it with VPNs.

Leading a group of people who have never met each other is challenging, the project managers say. “Many people came out good ideas, but few knew how to achieve it,” said Zeng.

Before the birth of OpenSourceWuhan, Zeng worked with Wuhan2020, which provided real-time data for hospitals, factories, procurement and other related parties, according to their official introduction.

“At the beginning, I just do my little bit to help,” he said, “then I found their objective was too grand. I didn’t know what they truly want at that time.” Lacking clear goals and effective management, Zeng said, is a problem for many volunteer projects.

As a game developer, Amo took a page from her career in her management style

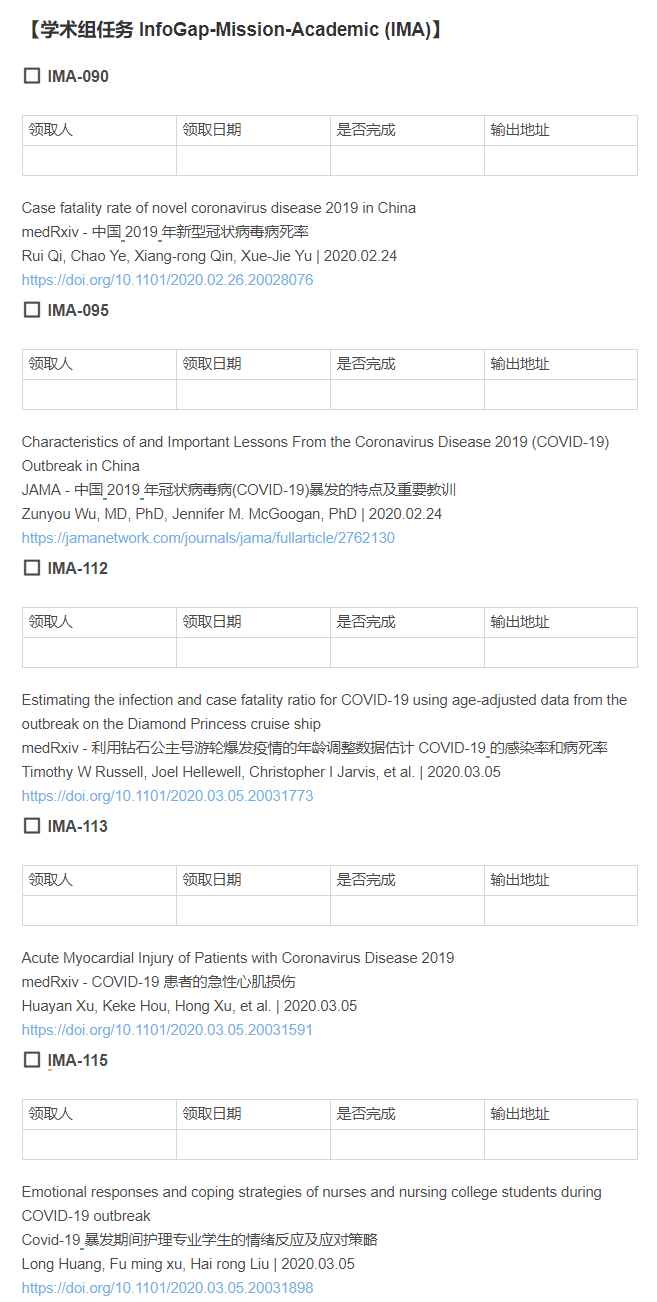

“You can see many tiny tasks in any video game,” Amo said. “If you complete them, you will get positive feedback.” This mechanism, Amo thought, stimulates people to complete new tasks constantly.

“So, I designed a ‘mission hall’ for my team,” she said. The “hall” was an online document. Anyone in her team can post a task in the “hall”. People from two translation teams can choose tasks they like and complete them.

To keep the project running, Amo also introduced a minimum workload. “All members from two translation teams must commit to translating at least one article a week,” she said. Some quit because they could not do it. Those who stayed ensured that the project ran smoothly till today.

Many volunteers say their work led them to take a new look at the society they live in.

“I think it has motivated more people to care about public affairs,” Yeung said. “If I didn’t pay special attention at the beginning, I wouldn’t do so many things later,” she added.

“After reading so many articles, I saw many people’s lives and how they were affected by the epidemic,” Han said. “Everyone in the boundless world is related to me now. I suddenly had such a feeling.”

Amo paid more attention to social responsibility. She described the online volunteer project as a “make-up class.” “As one of the young people growing up on the mainland China,” she said, “I know very little on how to contribute to society.”

She said having empathy is a prerequisite for establishing a sense of social responsibility. “Everyone’s life now is affected by the coronavirus, so it seems that everyone has become more concerned about society,” she said.

But as the situation in China eases and many people return to work, online volunteer groups are gradually coming to an end.

Han’s project halted on April 26 without any statement. “This decision is based on security considerations,” he replied in a chat message.

The same thing also happened with Amo’s Academic-nCov after the issue 55 on April 22. “We stopped updating and deleted all things,” said Amo without further explanations. The project’s GitHub page is turned into “private” now, which means only team members can view.

On Telegram, Cyber Graveyard of Epidemic News’s last update was on April 24.

Zeng changed his page name to Open-Source-COVID-19 and he has shifted to a global pandemic perspective. He has created a new section to place open-source projects, dashboards and statistics from all over the world. Now, his website has a collection of links of 237 projects.

“In fact, ‘withdrawal’ is also a very important part in volunteer activities,” A Xia wrote when she decided to stop updating, her project. “Rather than ending inexplicably, it is better to exit at an appropriate time.”

If you visit other people today, the virus will visit you tomorrow.

Academic-nCov issue 26 includes adacemic articles, WHO reports and news stories from US media.

COVID-19 Catalogue of Firsthand Information & Popular Science Articles is an open source project launched on GitHub, a popular site for coders to collaberate.

The Cyber Graveyard of Epidemic News publishes censored media news and individual social posts about the coronavirus.

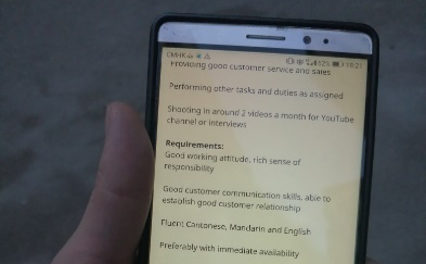

Academic-nCov includes a “mission hall” for volunteers to post “tasks”.

Everyone in the boundless world is related to me now.

Burned out Chinese teachers struggle with school responsibilities

It’s after 10pm and the city streetlights have long been on in southeastern China. Melisa returns home, exhaustion written on her face. All she wants is a shower

The unseen creators: how AI powers the mini-games becoming online hits in China

In three quick strokes, a blue-haired swordsman unleashes curved, shining blue blades for an attack that appears effortless as it takes down three masked opponents. Moments later, the swordsman stands still with a steely gaze and a calm face.

Loneliness drives new ‘accompanying economy’

Solo travelers hire “photo companions” for travel pics and conversation