Burned out Chinese teachers struggle with school responsibilities

More than 80% of surveyed teachers reported work stress.

By Li Xinyue

November 2024

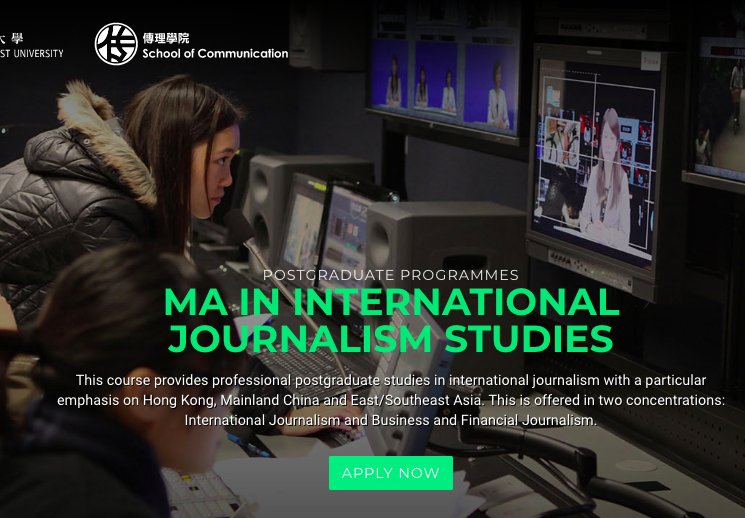

Jessie Ma’s mother, a teacher, works with a student in a home visit in Northwest China. Photo courtesy of Jessie Ma.

It’s after 10pm and the city streetlights have long been on in southeastern China. Melisa returns home, exhaustion written on her face. All she wants is a shower.

But it is too late for hot water to be available in the dormitory building she shares with her students, so she must make do with the warm water she stored earlier in an insulated bucket. Bath done, she still has a long way to go before making it to bed.

“Around 10:30 pm, I need to go downstairs to patrol the building to see if all the students are settled down,” Melisa said.

She knows she must speed up her pace if she has any chance of getting a bit more sleep herself.

Melisa, who agreed to speak only if her full name was not used because she fears losing her job, says she graduated from university in June 2024. Three months later she completed a competitive exam and successfully became an English teacher and head teacher at this boarding high school in a small city in Fujian province.

After only five hours of sleep, Melisa has to get up and to the sports field to monitor her students running in a morning exercise.

Like many teachers in mainland China, Melisa says she feels more pressure outside the classroom than she does during actual lessons. Teachers report being overstretched to meet the expectations of schools and parents who pile on too many responsibilities.

Every week, Melisa teaches 16 classes including sessions, morning and evening study classes as well as study groups. She says she cannot count on much rest on the weekends.

Melisa is also expected to stay in regular contact with parents.

“I’m in a boarding school, and parents are eager to know their kids are okay,” Melisa said.

Melissa talks to parents in WeChat messaging groups, with parents directly messaging her to check up on their children or asking her to pass them messages.

Melisa, like almost every teacher in China, uses instant-messaging apps constantly to communicate with families. Melisa said many parents also prefer calling teachers on the phone to discuss their children. A few times, she also needed to hold private sessions with parents to teach them how to use an online system that allows them to put money into their children’s canteen cards.

One day, after finishing class, Melisa walked into her office and threw herself into a chair and turned on her phone hoping for some enjoyable distraction. Instead, she found a WeChat message from a parent asking why the system still didn’t work for him.

Melisa said she sometimes can’t summon enough energy to organize a friendly reply.

“Sometimes they don’t consider whether teachers are busy or resting,” Melisa said. She also acknowledged that some students are not allowed to use their own mobile phones.

Melisa says that while she thinks most parents are reasonable and respectful they often expect her to solve every problem a child faces.

Melisa’s experience is a sharp contrast from the previous generation of teachers before messaging apps. Li Yingchun, who taught in a rural primary school in Fujian Province from 1992 to 1997, said, the biggest problem then was that he often could not find the parents.

We didn’t have mobile phones at that time, so we didn’t have many ways to communicate with the families,” Li recalls. “But I could feel the trust from them.”

More than 3,000 kilometers away in China’s northwest, Jessie Ma, the daughter of an experienced Chinese teacher at a public primary school, said she grew up watching her mother dedicate herself to her job. Jessie said her mother negotiated with bookstores to get parents some free teaching materials. Sometimes she even used her own money to pay for classroom items.

“If it were me, I wouldn’t choose to be a teacher,” Jessie said.

Almost 30% of teachers in China reported feeling emotionally exhausted, according to recent research that surveyed 42,000 teachers in China. More than 80% reported they suffered from work stress.

Xiong, an official handling basic education admissions in the southeastern province of Fujian who declined to give his full name, said to raise the quality of home education, officials plan to train teachers through seminars and strengthened home visits. Xiong had no response, however, when asked how authorities plan to improve the cooperative relationship between schools and teachers.

For Melisa, the end of the day brings worry about what new tasks she will face in the morning. But despite her exhaustion, she says still does not consider her situation entirely bad.

Standing in a hall of the dormitory building, she looks to see the morning glow already rising over the nearby mountains. It is time to go to the sports field. Three months ago, she admits, she was a young woman who still slept until noon.

“I just hope the school and parents can give us more understanding,” Melisa says, adding that she still expects things will get better in the future.

If it were me, I wouldn’t choose to be a teacher.

The unseen creators: how AI powers the mini-games becoming online hits in China

In three quick strokes, a blue-haired swordsman unleashes curved, shining blue blades for an attack that appears effortless as it takes down three masked opponents. Moments later, the swordsman stands still with a steely gaze and a calm face.

Loneliness drives new ‘accompanying economy’

Solo travelers hire “photo companions” for travel pics and conversation

Facing Death: A young mortician in China

A young mortician in China provides “dignity for the dead and comfort to the living.”